Unfinished Selves: The Layered Identities of Kudzanai-Violet Hwami and Anju Dodiya

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami and Anju Dodiya, engage the contemporary condition in which identity is expected to be legible, instantaneous, and emotionally accessible. Against this demand for clarity and coherence, both artists articulate a different proposition: that the self is layered, contingent, and continually in formation. Their work challenges the logic of recognition that dominates both social and aesthetic registers, proposing instead that subjectivity can be understood through opacity, fragmentation, and multiplicity.

Although Hwami and Dodiya work within distinct geographies, mediums, and visual vocabularies, their practices converge in an insistence on resistance to being easily read. Each treats representation not as revelation but as a process of negotiation. Through different material strategies, both artists unsettle the expectation that visibility must coincide with understanding, or that to be seen is to be known.

Hwami’s paintings often originate from an accumulation of images drawn from personal archives, digital repositories, and diasporic experience. These elements combine to form compositions that function as mnemonic cartographies, where memory, imagination, and displacement coexist in unresolved tension. Her integration of digital manipulation with painterly gesture produces surfaces that blur distinctions between temporal and spatial registers. In Hwami’s work, the past and present are not sequential but coextensive; history becomes something that can be revisited, revised, and reinhabited.

During a public talk, when an audience member asked Hwami whether her work was “about the Black body,” she replied, “Yes it is, but I don’t know why I have to disclose that.” The remark encapsulates her ambivalence toward the demand for self-disclosure that often shadows artists racialized by the art world’s gaze. It articulates a refusal of compulsory legibility, suggesting that the insistence on naming or explaining one’s subject position can itself become a form of containment. In this sense, Hwami’s practice performs a politics of withholding, transforming opacity into both a formal and ethical position.

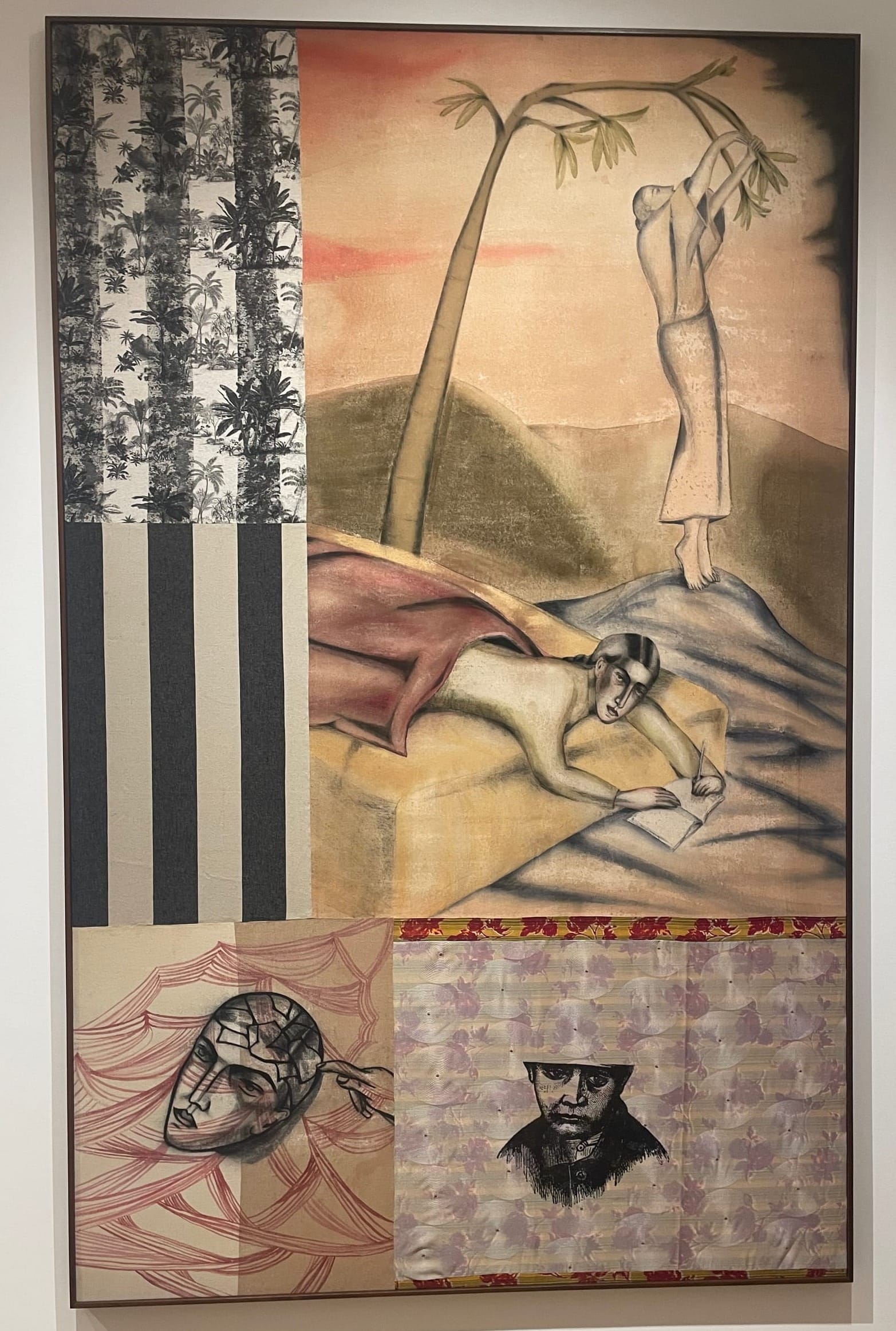

Dodiya, in a different register, turns toward the psychological interior. Through watercolor, textile layering, and a restrained yet expressive figuration, she constructs spaces of contemplation and withdrawal. Her figures often appear caught in moments of introspection or quiet fracture, suggesting the psychic labor of selfhood rather than its performative display. Drawing on mythological and domestic references, Dodiya situates the individual within a complex network of historical and emotional inheritances. The theatricality of her mise-en-scène does not produce spectacle but a heightened sense of interiority, where vulnerability becomes an act of resistance against the expectation of transparency.

Considered together, the work of Hwami and Dodiya offers a critical framework for examining how representation operates under conditions of hypervisibility and surveillance. Both reject the assumption that the self, particularly for women, queer subjects, or those shaped by diaspora, must conform to expectations of clarity or coherence. Their practices privilege opacity as an ethical mode and fragmentation as a strategy of survival. By doing so, they propose that identity need not be resolved to be real, and that the refusal to be fully seen can itself constitute a form of agency.