In the Space Between: The Liminal Worlds of Yiadom-Boakye, Johnson, Toor, and Zhang

In a world defined by constant movement, translation, and exchange, the question of identity, of who we are and how we relate to others—has become increasingly complex. The artists shaping contemporary art today often operate across geographies and disciplines, navigating multiple worlds at once. Their work captures what theorist Homi Bhabha calls liminality, a condition of in-betweenness where identity is neither fixed nor singular but continuously negotiated. In this liminal space, which Bhabha describes as the “third space,” culture is not something inherited but something in the process of being made.

In parallel, Édouard Glissant’s idea of mondialité offers another way of understanding this condition. Writing in the late twentieth century, Glissant argued against both the flattening of globalization and the closures of nationalism. Instead, he proposed a poetics of relation, a world where difference coexists without hierarchy and where identities are formed through contact rather than isolation. Taken together, liminality and mondialité describe the lived realities of artists who move through complex networks of belonging, memory, and influence, artists whose practices refuse singular definitions in favour of openness and multiplicity.

This intersection can be traced in the works of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Rashid Johnson, Salman Toor, and Vivien Zhang. Each of these artists visualizes what it means to inhabit a shifting world of relations. Their practices, spanning painting, installation, and material assemblage, explore how personal and cultural identities are constructed in the spaces between histories, media, and experience.

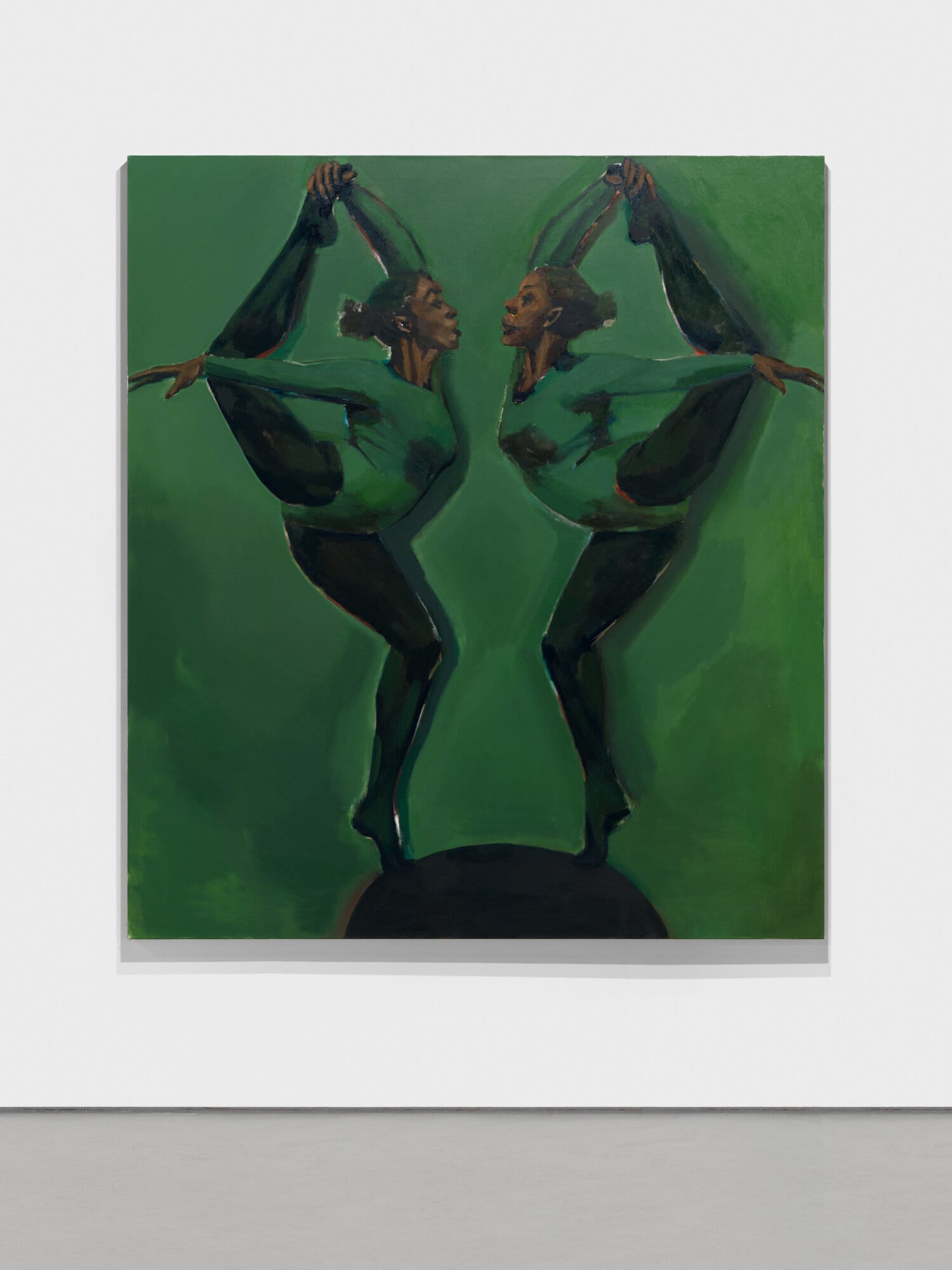

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings represent a liminality of imagination. Her figures are fictional, yet they feel deeply present. They exist outside of time and geography, occupying a psychological space between reality and invention. By refusing portraiture, Yiadom-Boakye resists the notion that identity must always be explained or visible. Her figures embody Glissant’s “right to opacity”,they are not meant to be decoded but encountered. In this sense, her work is relational rather than representational. Each painting invites the viewer into a suspended moment of becoming, where identity remains fluid and unfixed.

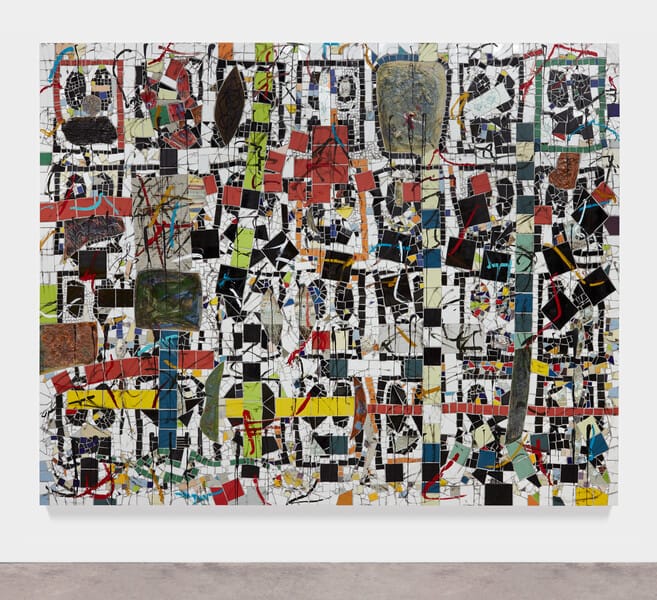

Where Yiadom-Boakye approaches identity through imagined interiority, Rashid Johnson grounds it in material form. Using shea butter, black soap, and tiled surfaces, Johnson constructs tactile environments that move between personal ritual and collective memory. His work speaks to the complexity of African American identity, its inheritance of trauma and its capacity for regeneration. Yet Johnson’s assemblages are not nostalgic; they are forward-looking, using material as language. Through repetition and accumulation, his installations visualize what Glissant might describe as a poetics of entanglement, where meaning is built through layers of relation rather than linear history. In Johnson’s world, materials act as archives of emotion, belief, and resistance that remain constantly shifting and alive.

Salman Toor explores another dimension of this relational condition, the emotional and social liminality of diasporic life. His figures occupy domestic interiors and social gatherings that oscillate between comfort and unease. They inhabit what Bhabha terms the “unhomely,” where belonging and alienation coexist. Toor’s scenes of queer, diasporic life move between Lahore and New York, between cultural codes and emotional registers. The light in his paintings—green, theatrical, or softly golden, amplifies this sense of psychological in-betweenness. His compositions are intimate but never entirely safe, mirroring the vulnerability of living between worlds. Where Yiadom-Boakye imagines new subjectivities and Johnson materializes collective histories, Toor renders the emotional texture of diaspora—the internal negotiation of self within shifting social frames.

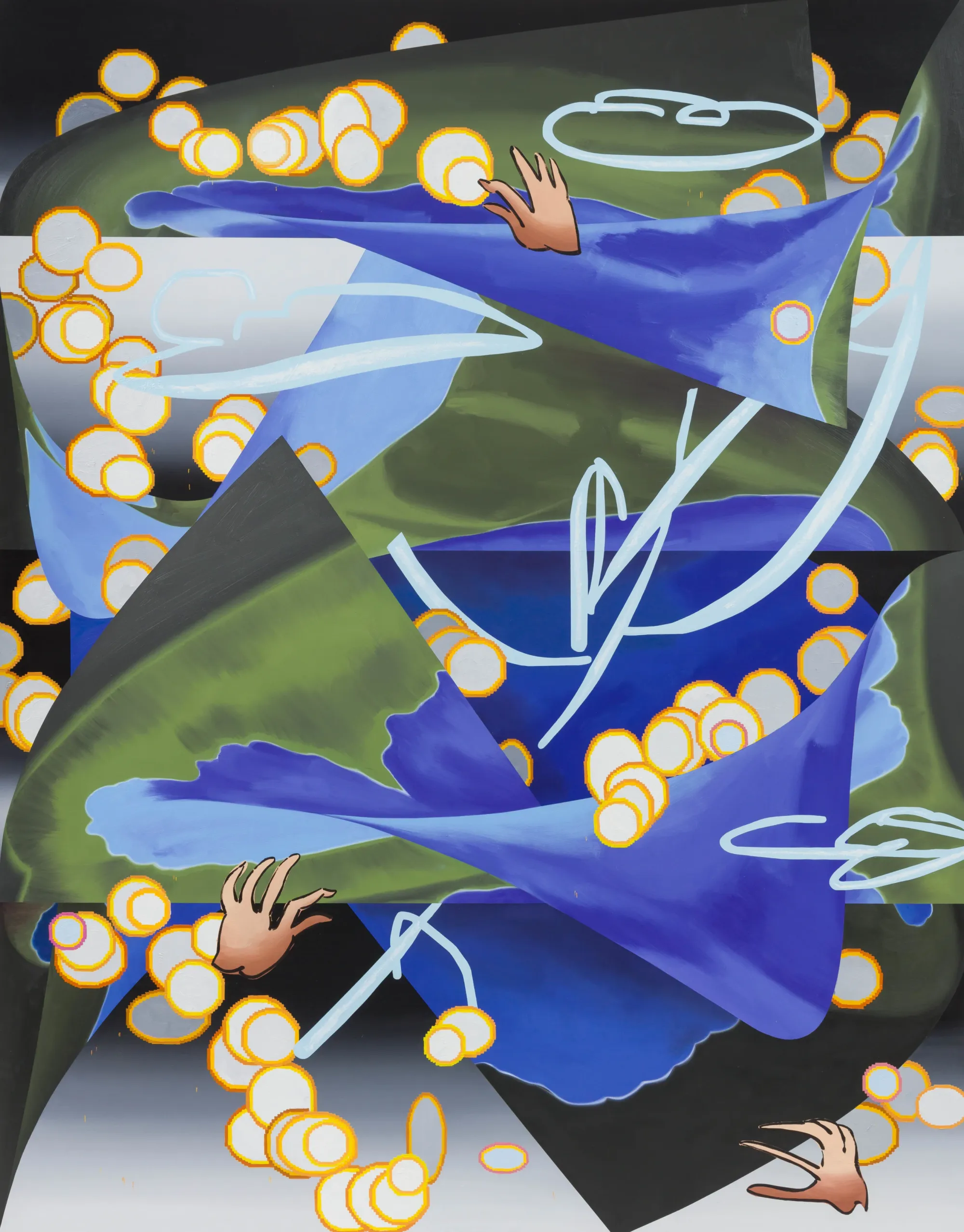

Vivien Zhang brings these questions into the realm of image circulation and digital culture. Her layered compositions combine visual languages from different systems, including Chinese motifs, scientific diagrams, and internet icons, to create spatial maps of global exchange. Zhang’s work reflects how meaning travels, mutates, and loses origin in the digital age. Through repetition and variation, she turns painting into a site of translation, a way of visualizing the instability of context itself. In doing so, she extends Glissant’s mondialité into the twenty-first century, revealing how, in our networked reality, everything is connected yet constantly shifting.

Together, these artists form a conversation about how we live and see in a world of movement and relation. They occupy what might be called an aesthetic of the in-between, where identity is not a fixed statement but an ongoing negotiation. Each engages a different form of liminality—psychological, material, emotional, or digital,yet all share a refusal to be reduced. They insist that art, like identity, is made richer by its contradictions.

Ultimately, their works remind us that to live in relation is to accept complexity, to recognize that belonging can be multiple, that visibility can coexist with opacity, and that freedom often emerges not from certainty but from openness. Through their practices, Yiadom-Boakye, Johnson, Toor, and Zhang reimagine what Glissant once called “the world’s totality of relation,” a world still fragmented yet full of connection, care, and possibility.