Figures in Suspension: Richard Avedon and Peter Doig

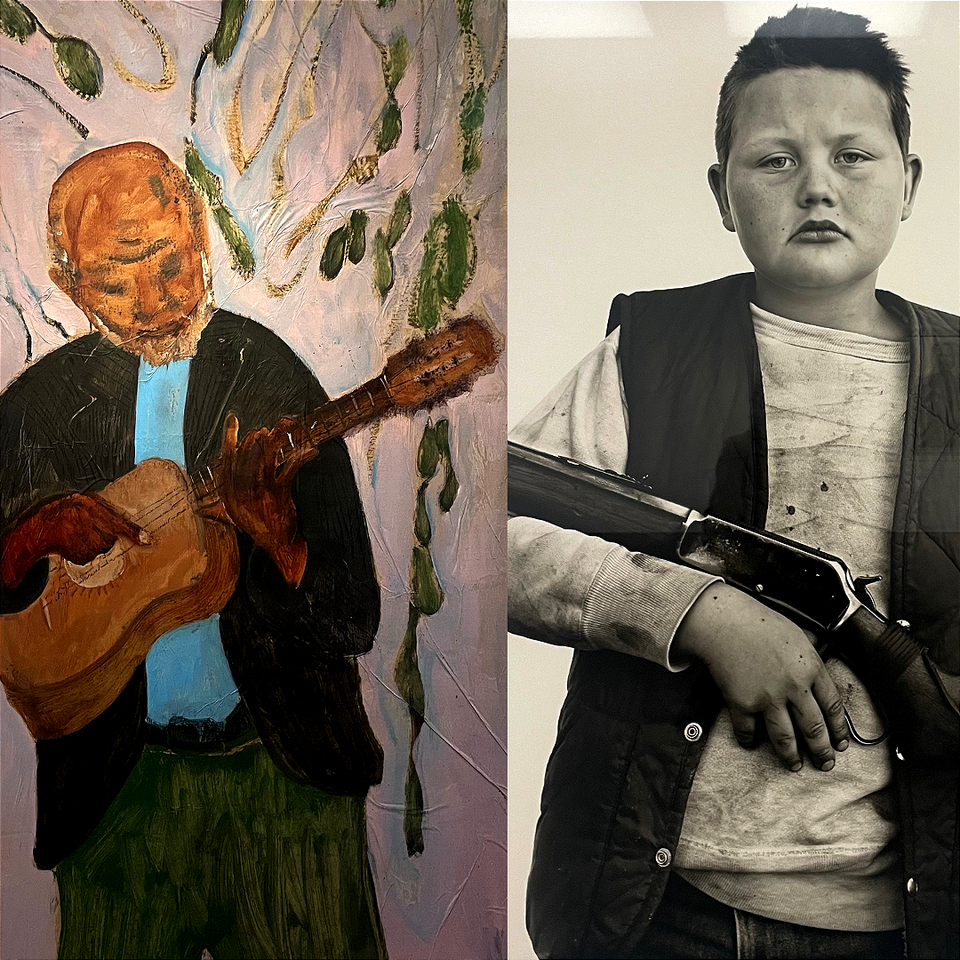

Seeing the exhibitions of Richard Avedon in Gagosian and Peter Doig in Serpentine South right after another first feels like an unlikely pairing. One works in photography, the other in painting. One confronts the viewer with stark clarity, the other drifts into ambiguity and atmosphere. Yet placed side by side, their work begins to feel like two different ways of thinking about what it means to be human.

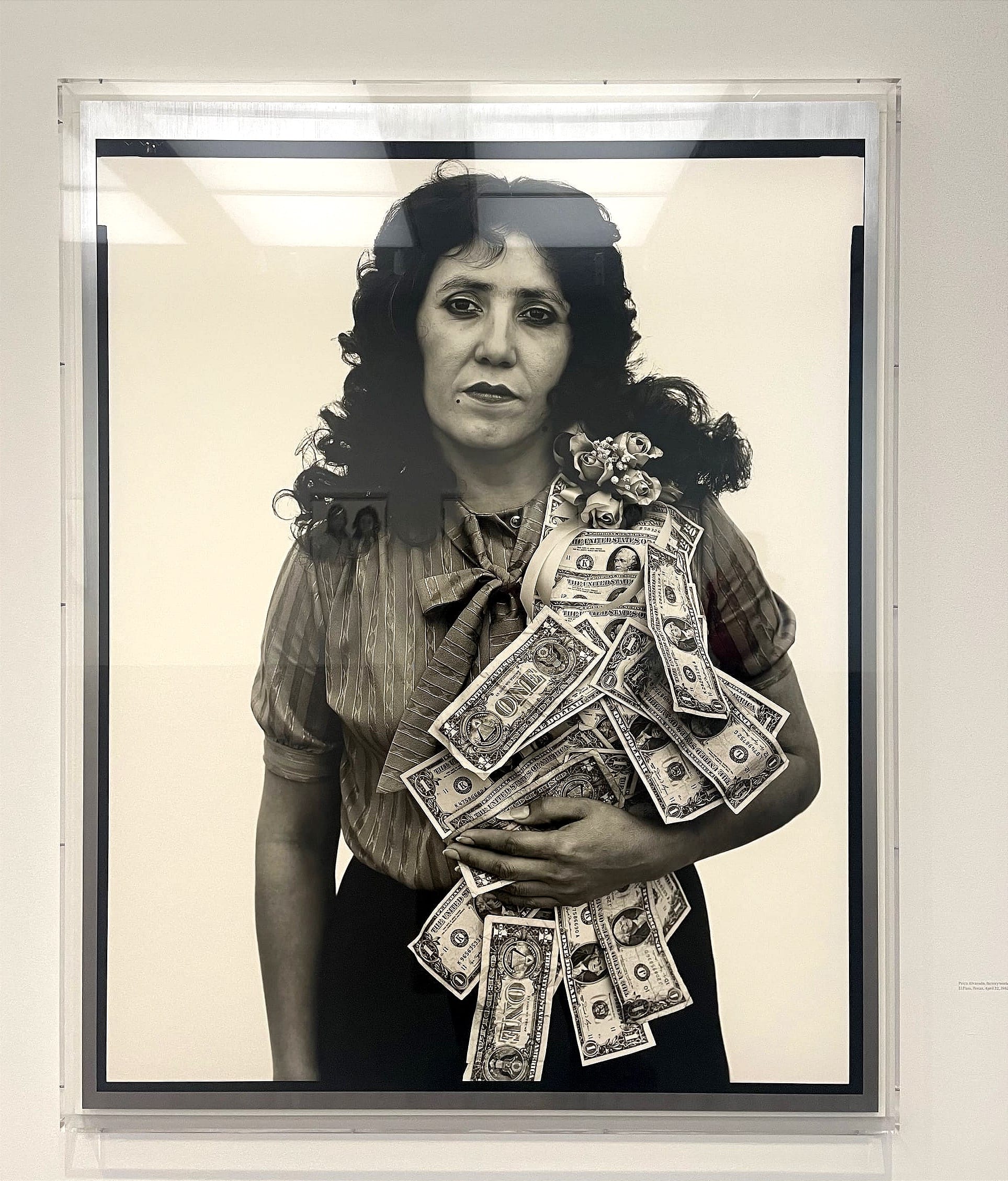

Avedon’s portraits are defined by sharp focus, high contrast and a stripped back setting. His subjects stand alone against blank backgrounds, their clothes and objects such as guns, flowers and banknotes becoming clues to their social world. These images feel direct and unprotected. The camera seems to insist on visibility, fixing each person in a moment of exposure. We do not encounter them as private individuals but as social figures shaped by work, class and circumstance. There is something confrontational in this clarity, as if the photograph forces both subject and viewer into an uneasy exchange of gazes.

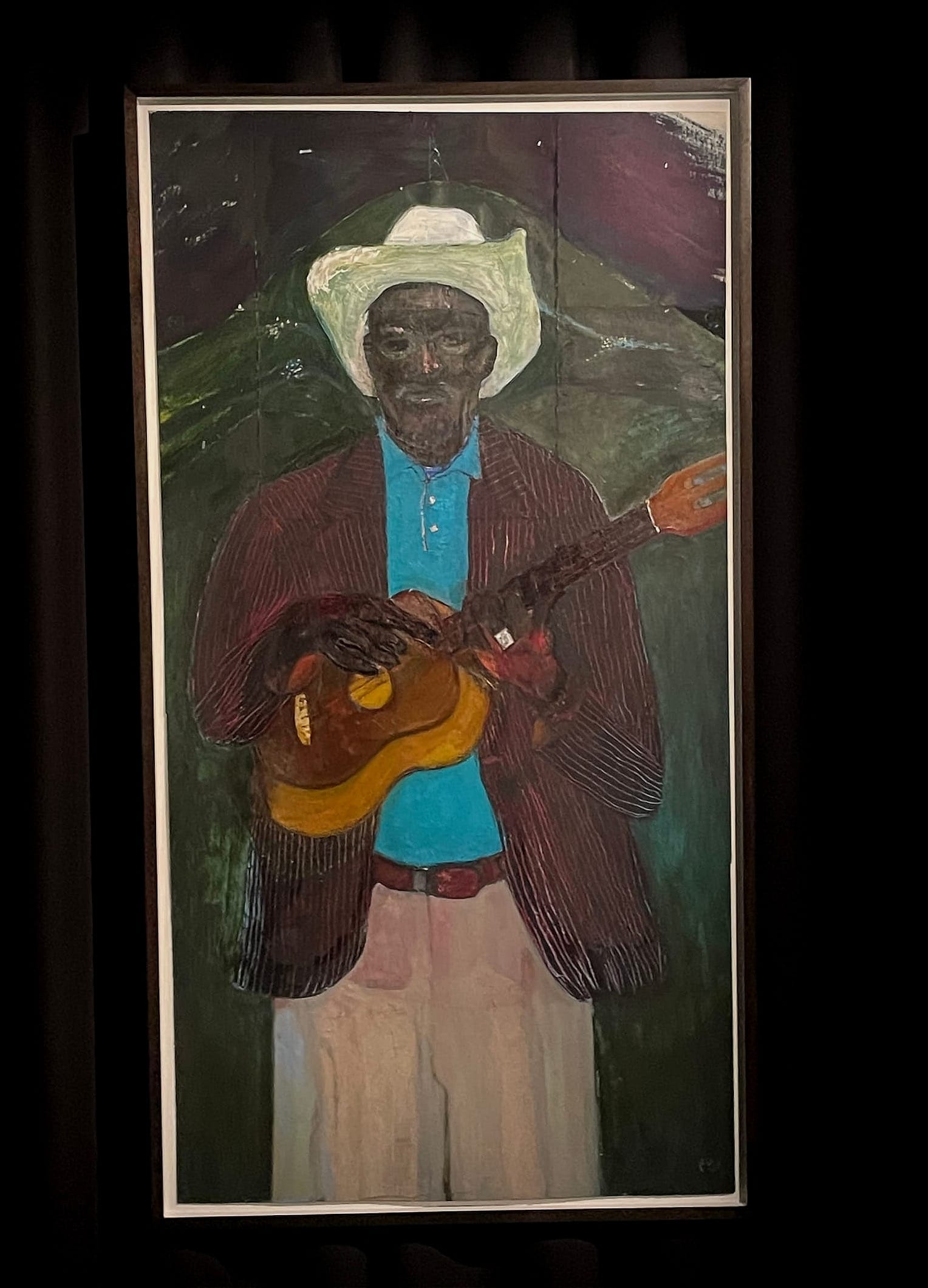

Doig’s figures, by contrast, seem caught in a moment of inner drifting. Rather than confronting the viewer, they recede into environments that blur into memory or imagination. Their forms are softened by layers of paint, and their actions appear unfinished, as if occurring within a private mental space rather than in the visible world. This suspension feels inward rather than outward. The figure is not held in place by the gaze of others but by its own perceptual and emotional atmosphere, hovering between presence and disappearance.

Despite their differences, both artists detach the figure from clear storytelling and turn it into something closer to a philosophical question. Avedon’s people become signs of social reality, while Doig’s become expressions of mental or emotional states. Both convey a sense of alienation, though in different ways. In Avedon’s work, alienation appears through exposure and visibility. The subject is defined by how they are seen. In Doig’s, alienation takes the form of solitude and interiority. The figure drifts within its own perceptual space. Together, they give me a sense that one of the central dilemmas of human experience lies between two uneasy conditions: being fixed by the gaze of others and being lost within one’s own thoughts and memories.

I am not claiming that Avedon and Doig share a style or intention. Rather, seen together, their work reveals two different ways of thinking about human presence. Neither state is fully livable on its own. To be seen too clearly is to risk becoming an object, defined from the outside, while to retreat entirely inward is to risk disappearance. Between these poles, human presence exists as a fragile balance, a continual negotiation between visibility and inwardness, between the world that names us and the inner life we can never fully show. Avedon’s photographs propose a condition of exposure, in which identity is shaped through social visibility, while Doig’s paintings propose a condition of interiority, in which identity remains fluid and uncertain, unfolding through memory, mood and sensation. Between these two modes emerges a broader reflection on the human condition, not as a fixed state but as a tension between being seen and being felt.

Looking at Avedon and Doig together, I feel they offer two different ways of understanding the human condition. Avedon shows identity as something shaped from the outside, through social roles and the act of being photographed, while Doig shows it as something shaped from within, through memory, sensation and mood. Between these two positions, identity appears neither stable nor fully fluid. What remains is not a definition of what it means to be human, but a space to think about the tension between inner life and outer appearance. This space feels closely aligned with the spirit of Animira, rooted in anima, meaning soul, and mira, meaning wonder. It is a way of seeing that moves between emotional depth and cultural reality, where art becomes a meeting point between lived experience and reflection, and where questions of identity, presence, and belonging can be held open rather than resolved.